Before there was an East-West Tollway, before there was a Kennedy Expressway, before there was even a State Street, there were a number of longtime--if not ancient--ways to get around the Chicago area. These routes were primitive, fairly rugged, unmarked and probably without names. Nonetheless, they helped hundreds of thousands of Native Americans traverse Chicago and the Midwest for possibly tens of thousands of years.

Today, these Native American trails are all but forgotten, recognized only by a handful of major thoroughfares that follow their routes. "Most Chicagoans would have no idea that they're traveling on what used to be an Indian trail," says Russell Lewis, deputy director of collections and research for the Chicago Historical Society. "It's sort of sad," he adds. "You have honorary signs for a lot (of historic sites) around Chicago, but no one has made a note of these trails."

Some of the more well-known Chicago area roads that are on or near Native American trails are Sauk Trail in the far south suburbs, Green Bay Road on the North Shore, Deerpath Avenue in Lake Forest, Ridge Avenue in Evanston, and Archer Avenue, Clark Street, North Michigan Avenue, Grand Avenue, Elston Avenue and Vincennes Avenue in Chicago.

Except for Sauk Trail, all the routes have been renamed in honor of people or things other than Native Americans. The trails, though once simple footpaths, were fundamental in Chicago's development, say historians. "I think we owe the Native Americans a great debt," says Lewis. "They really understood Chicago's geographic importance and took advantage of that."

"Chicago might not have progressed as much as it did without the work of the Native Americans," says Michael Stachnik, archivist for the Ridge Historical Society in Chicago's Beverly Hills-Morgan Park neighborhood. Of the dozen-plus trails in the Chicago area, the route that was to become Vincennes Avenue was typical of the way trails evolved, say historians.

The roots of the Vincennes Trail were formed 10,000 or so years ago when the glaciers receded from the area that was to become Chicago, carving out valleys, hills and moraines. One of the ridges formed by the glaciers traveled south and west from what is now the center of Chicago. When the first Native Americans explored the area, the ridge was a natural route. "Basically the Indians made use of the higher terrains so they didn't have to work their way through marshlands and wetlands," says Stachnik. From what little history has been culled about the Native Americans of the area, it is known that tribes such as the Illini, the Fox (who were called the Sauk by the French) and later the Potawatomi used the Vincennes Trail for a variety of reasons. "A lot of these trails were used just for moving through the Chicago area, say from Wisconsin in the summer to southern Illinois in the fall," says Stachnik. "Few tribes lived in what is now the Loop area as it was all marsh." "A lot of these tribes were semi-sedentary," says Lewis. "They would move from season to season and would use the trails to get to the various hunting and fishing areas. "There were also political alliances among the tribes," adds Lewis. "And the Native Americans would use the trails to visit each other. These were roads like our roads."

The Vincennes Trail ran from what is now downtown Chicago, southwest through the city, passing through neighborhoods such as Auburn Park, Beverly and Morgan Park. It then ran through Blue Island before heading east and south some 200 miles through Crete, Hoopeston and Danville and to Vincennes, Ind., on the Wabash River. From there, it split into two trails. When the first white explorers and settlers came toward Chicago from the East in the late 1600s and early 1700s, it was not surprising that they found their way to the Vincennes Trail, says Stachnik. "You have this path from hundreds if not thousands of years of occupation that's beaten down so it's fairly obvious," says Stachnik. "It was easy to link up with the trail because there was so much wetlands around."

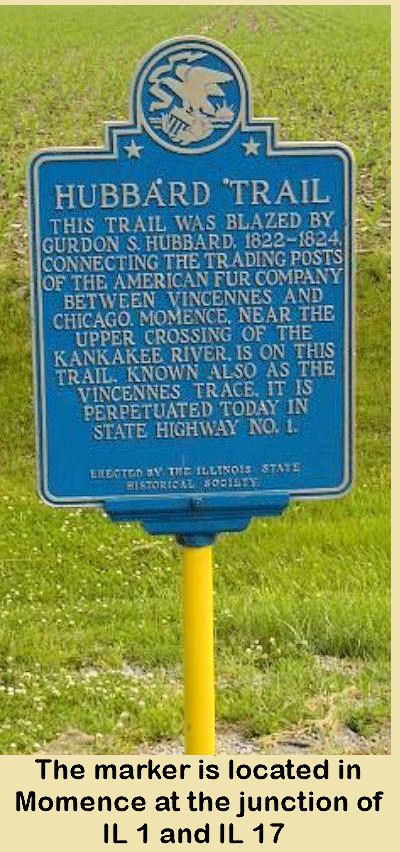

By the 1820s, Chicago was burgeoning. The Vincennes Trail, basically State Street to Vincennes to Winchester Avenue to Western Avenue, was a main route for trappers and traders traveling to Ft. Dearborn to barter and for access to the Great Lakes. Early residents named the trail for its connection to the Indiana town and usually called the route the Vincennes Trace. The Indiana town was named for the French-Canadian explorer, Francois Margane Sieur de Vincennes, who built a fort on the Wabash River in 1731. The route was also known as the Hubbard Trail for Chicago fur trader Gurdon S. Hubbard.

As the city grew, the Vincennes Trail would become a stagecoach route, and small inns, such as the Rexford House at 91st Street and Pleasant Avenue in Chicago, sprouted up along its route. In 1834, the trail was declared a state road by the Illinois legislature but was later abandoned with the advent of the railroads. The name stuck for the route's northern tip--now State Street.

By the mid-1800s, the waterways and railroads had replaced foot and wagon travel as the primary way to move people to Chicago. The trail, however, became an important avenue for farmers south of the city. In 1854, it was moved a few blocks to the east, parallel to the tracks of what is now the Rock Island Railroad and upgraded. "Farmers would use this trail to take their wares into Chicago to a large market along Lake Street," says Stachnik. According to local history reports, the trail was then marked with a large stone sunk into the ground every mile or so.

By the end of the 1800s, most Native Americans were displaced from the Chicago area. Yet, their trails, such as the Vincennes, were in use more than ever. In the early 20th Century, with the advent of the automobile and the move to improve roads, the Vincennes Trail became Vincennes Road and later Vincennes Avenue, a major artery southwest from the Loop. As it was improved, however, the route was again moved, mostly to the east. "As city officials drained water off the land, they were able to make more direct routes of roads like Vincennes," says Stachnik.

Today, other than the name of the modern-day road, the only recognition that the Vincennes Trail has garnered is a small stone and plaque erected in 1928 by the Daughters of the American Revolution. The stone sits near the original location of the trail at the southeast tip of the Dan Ryan Woods Forest Preserve at 91st Street and Pleasant Avenue. "It's hard to imagine where we would be without the trails and the Native Americans," says Stachnik. "Not only did they show us where to hunt and what to eat, but where not to step."

Though numerous roads in the Chicago area have their roots in Native American trails, each route has its own significant history. Some examples:

- Green Bay Road was a centuries-old Native American trail used extensively by tribes such as the Potawatomi and the Fox. In the early 1800s, white settlers spent decades straightening the zigzagging trail each winter using a sled through the snow to mark the new route for travelers in the spring. The Green Bay trail began in Chicago at the north end of the Michigan Avenue bridge, traveled up what is Rush Street and then over to Clark Street and north out of the city. Alternative Indian trails to Green Bay out of what is now downtown Chicago were what are now Elston and Milwaukee Avenues. In 1832, Congress approved a road to be built over the trails.

- The Great Sauk Trail connected Rock Island to Detroit and ran near Chicago. It is now Sauk Trail in the south suburbs. It was a favorite of early European settlers who preferred an overland route to the unpredictable and sometimes fatal trip by ship on the Great Lakes. These travelers would reach Detroit via Lake Erie and head southwest on the trail, coming near Lake Michigan at Michigan City, Ind. It also was used by soldiers in the early 19th Century as a route between military garrisons in Chicago and in Ft. Wayne. In the 1820s, the U.S. government signed a treaty with local Native Americans that allowed them to turn the Sauk Trail into a road.

- Army Trail Road was at first a Native American trail that traversed what is now the western suburbs. In the Black Hawk War, Gen. Winfield Scott and his army followed the trail to Beloit, Wis. Hence, its current name. The trail also connected to the Kellogg Trail, which led to Galena. Both became the first state road from Chicago to Galena, along which the first Chicago-Galena mail route was established in 1834.